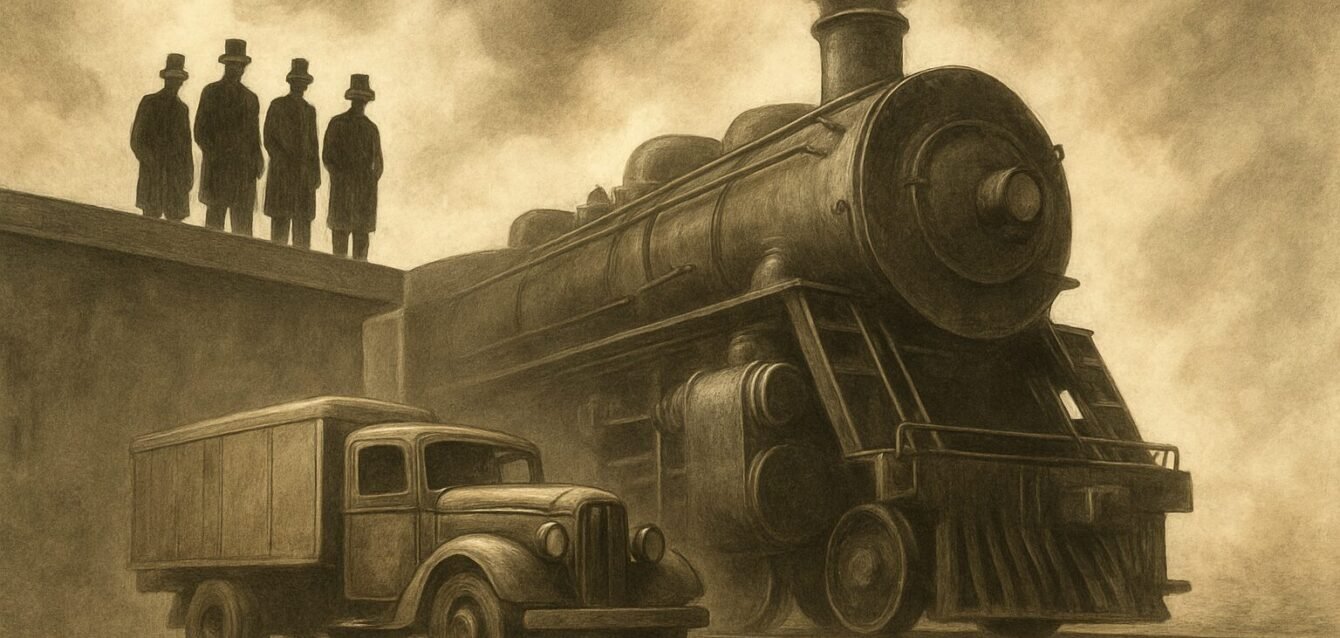

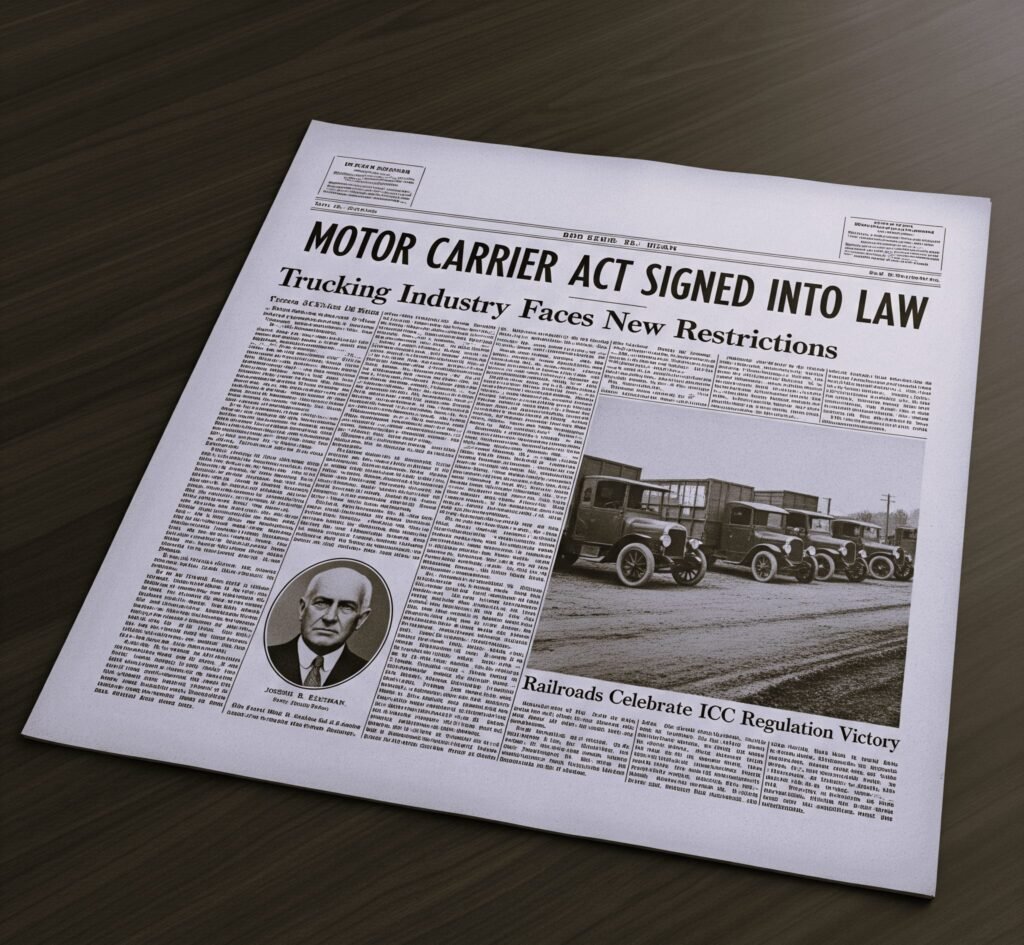

Major historical shifts often stem from pivotal legislation. In the case of freight trucking in the U.S., that legislation was the Motor Carrier Act of 1935, a law that significantly restricted the freedom of the trucking industry and protected the profits of the railroad elite. What was once a free market in freight shipping was brought under the thumb of regulation, with long-lasting consequences.

The Act That Changed Everything

When the Motor Carrier Act went into effect on October 14, 1935, it marked a major turning point. Trucking companies were now required to apply for permits, certificates, and licenses from the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) within 120 days. These applications were complex and burdensome, making it nearly impossible for new trucking companies or independent operators to break into the market. Only existing companies could manage the process, effectively closing the door to new competition.

Meanwhile, railroads, which were not subjected to such regulation, stood to benefit. The act’s passage was celebrated by railroad executives like F.E. Williamson of the New York Central Railroad, who openly stated that the law would “equalize competitive conditions,” a clear acknowledgment that the purpose was to limit trucking’s growing influence in freight transport.

Regulatory Overreach and Biased Enforcement

By April 1936, truckers were already pushing back against the Act’s unfair restrictions. Yet their efforts were ignored. The ICC, heavily aligned with railroad interests, retained complete control over rate-setting, working conditions, and safety regulations, exclusively for truckers.

Truck drivers and shipping companies organized town halls, such as those led by the Shippers Conference of Greater New York, to protest the stranglehold the ICC had on the industry. They demanded the right to set fair and independent freight rates without railroad interference. But their resolutions went unheeded.

In 1938, the ICC proposed amendments to the Act that would expand its power even further. These included allowing the Commission to act on freight cases without public hearings and giving it authority to revoke licenses or dissolve companies deemed unlawful, without due process. One ICC member even remarked that truckers “need much instruction,” further highlighting the dismissive attitude toward the industry.

These actions directly violated the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, yet were pushed forward in the name of “efficiency.” The new rate bureau system required truckers to submit proposed freight rates 30 days in advance for ICC approval, rates which the Commission, often staffed by individuals with ties to railroads, could change at will.

Monopoly by Design

The railroads didn’t stop at regulation. In 1937, a proposal by the Motor Rail Company (a Pennsylvania Railroad partner) sought to allow a company to operate both rail and trucking freight, giving it access to privileged rate structures that no independent trucking firm could match. This further entrenched the power of those aligned with railroad companies.

The Act also imposed freight and route restrictions that limited what goods truckers could carry and forced them to take longer, more expensive routes. This directly undercut the key advantages of trucking: lower costs and access to areas railroads didn’t reach. Worse still, companies that partnered directly with railroads were exempted from many of the restrictions. These railroad-aligned trucking companies were no longer regulated under the Act but by the ICC directly, granting them operational freedom denied to others. This created a two-tiered system, one for those aligned with railroads, and another for the rest, who were left to struggle under regulatory oppression.

The Long Road of Subjugation

Despite mounting resistance, the trucking industry remained under these suffocating conditions for decades. The passage of the Reed-Bulwinkle Act of 1948 further reinforced the status quo, giving additional protections to rate bureaus and allowing more leeway for price-fixing under the guise of regulation.

From 1935 onward, the trucking industry became a battlefield for economic control, with wealthy capitalists and railroad monopolies using federal power to suppress competition. What began as an effort to stabilize transportation during a time of economic uncertainty turned into a 45-year campaign to subjugate the trucking industry, deny fair competition, and preserve the dominance of an aging railroad empire.

45 Years of Suppression

Railroads and their allies used these laws to protect their profits at the expense of America’s most adaptable, cost-effective freight solution. Independent trucking’s potential was systematically delayed for an entire generation. Truckers didn’t just face bureaucratic hurdles. They faced a systematic effort to suppress their freedom, profitability, and growth. For 45 years, the freight trucking industry endured government-imposed limitations that benefited railroad companies and their capitalist backers.

The tactics used in the mid-20th century are a warning for today: centralized control over freight infrastructure breeds inefficiency, limits competition, and harms the very workers who keep America moving. With the American Dream Rail Project, the future will be reinvented.